In the 1970s, I lived in group houses with a lot of interesting people. One of them had inherited an assortment of reel-to-reel tapes from his father. Eventually we acquired a reel-to-reel machine and began dubbing everything onto cassette. The reels were in poor condition, so this amounted to a rescue operation.

Some of the material was old jazz, some of it was old radio commercials; one reel contained a set of 1949 performances by John Lee Hooker that many years later got released as “Jack Of Diamonds.”

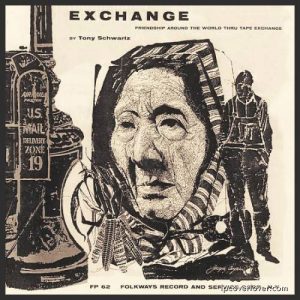

And one reel held this extraordinary document:

Tony Schwartz, master of electronic media, created more than 20,000 radio and television spots for products, political candidates and non-profit public interest groups. Featured on programs by Bill Moyers, Phil Donahue and Sixty Minutes, among others, Schwartz has been described as a “media guru,” a “media genius” and a “media muscleman.” The tobacco industry even voluntarily stopped their advertising on radio and television after Schwartz’s produced the first anti-smoking ad to ever appear (children dressing in their parents’ clothing, in front of a mirror). The American Cancer Society credits this ad, and others that followed, with the tobacco industry’s decision to go off the air, rather than compete with Schwartz’s ad campaign.

Born in midtown Manhattan in 1923, a graduate of Peekskill High School (1941) and Pratt Institute (1944), Tony Schwartz had a unique philosophy of work: He only worked on projects that interested him, for whatever they could afford to pay.

{snip}

For many years he was a Visiting Electronic professor at Harvard University’s School of Public Health, teaching physicians how to use media to deal with public health problems. He also taught at New York University and Columbia and Emerson colleges. Because Schwartz was unable to travel distances, he delivered all out of town talks remotely. Schwartz was a frequent lecturer at universities and conferences, and gave presentations on six of the seven continents (not Antarctica). He was awarded honorary doctorates from John Jay, Emerson and Stonehill Colleges.

{snip}

“Documenting life in sound and pictures” is something Tony Schwartz begin in 1945, when he bought his first Webcor wire recorder and began to record the people and sounds around him. From this hobby developed one of the world’s largest and most diverse collections of voices, both prominent and unknown, street sounds and music, a collection that resulted in nineteen phonograph albums for Folkways and Columbia Records.

During the 1950s, Tony Schwartz sent this recording out into the world, presumably under an early version of a Creative Commons license.

While I was already getting interested in what was then called “Ethnic Music,” this recording was something completely different — dozens of different songs from all over the planet, each introduced by the same voice.

I bumped into Tony Schwartz’ name a few times on various Folkways lps, but never learned much about the man until I started listening to the Kitchen Sisters’ wonderful “Lost And Found Sound” series — when I had a delightful shock of recognition. Give this audio portrait a listen.

Was there ever a more succinct demonstration of the boundless and gorgeous diversity of humankind’s music? Tony Schwartz did my youthful self a great favor by introducing me early on to the incredible variety of our species’ sonorous expression. Now, as I am increasingly preoccupied by environmental concerns, I return to the Tony Schwartz Tape as a motivating force.

Ethnomusicologists and collectors have done an admirable job documenting the world’s music. There is scarcely any cultural tradition anywhere that has not had its parameters outlined, its relationships with other genres delineated, its epistemologies investigated, its mysteries probed. But the traditions themselves are often in danger of vanishing in their natural habitats, eerily duplicating in the cultural arena the accelerated extinctions which industrialized humanity has accomplished in the natural world.

The Tony Schwartz exchange tape sensitized me early on to the boundless beauty of human music. How can we in good conscience allow this loveliness to be destroyed by our own greed and indifference?