I wrote this piece three years ago. Now the news of Pete’s passing fills my computer screen. While I will certainly write something later today about Pete and his influence, this is a good place to begin: with a song, and a protest, and a woman, and our future, and a child, and Pete.

=====================================================================

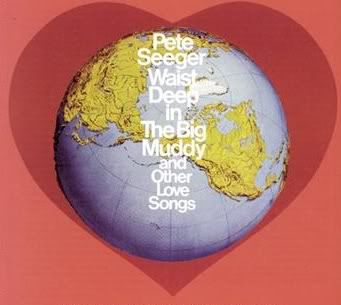

I think I was twelve when my parents gave me a new Pete Seeger lp. They knew I loved his music; I’d listened over and over to “We Shall Overcome: The Carnegie Hall Concert” and knew most of the songs, or at least their lyrics, by heart. I’d memorized most of the songs on the “Children’s Concert at Town Hall,” and forty years later I can get a good laugh from any kid by singing “Where have you been all the day long, Henry my boy?” with its gross, lugubrious “greeeeeeeeen and yeller” chorus.

But this was a new disc, and I’m quite sure my folks just went into the store and grabbed something off the shelf. After all, Pete had a lot of albums, and they were all pretty much the same, right?

Well, actually, no.

To the extent that I am actually able to think of myself as an activist — to the extent that I can trace my own history all the way from childhood and recognize at least the slow sprouting of a seed, I keep coming back to some songs on “Waist Deep In The Big Muddy, and other love songs.” Some of them I’d heard during summers at Camp Killooleet; our counselors sang a lot of Pete’s songs, and not just “Abiyoyo,” but “Big Muddy,” “Where Have All The Flowers Gone,” “Turn, Turn, Turn” and many others that were essential to that late-sixties zeitgeist. The camp itself was, wondrously, run by Pete Seeger’s older brother John, and it was overrun with Seegers, all without exception beautifully musical.

Anyway.

The songs on that record went into my mind early on, and have stayed there ever since. One or two of them I have performed on stage; many of them I sing for my own enjoyment and comfort.

And one of them has been a constant companion, for over forty years reminding me of the necessity of action, even when it seems hopeless.

Especially at those times, my reasons for activism are contained in that one of Pete Seeger’s songs.

It was brought home to me the other day as I was preparing for my most recent Climate Concert. I was in the kitchen, preparing food for the performers (they’re donating their time and artistry — the least I can do is cook for them!) and my wife came in to chat.

“You’re really killing yourself with these concerts,” she said, while our daughter’s voice came through the passageway as she told a story to herself in the other room. “Why do you feel so compelled to do this?”

I replied, “The reason is in a song.” And standing in the kitchen with my hands in a bowl of potato kibby, I sang.

*****************************************************************************

My name is Lisa Kalvelage,

I was born in Nuremburg

And when the trials were held there, nineteen years ago,

It seemed to me ridiculous,

To hold a nation all to blame,

For the horrors that the world did undergo.

“I don’t believe there is a god we can turn to in the time of need. As a humanist I feel I must do everything in my power to become involved in the issues of our time. If we have this conviction, we also will have the strength to make a difference.”

Lieselotte “Lisa” Kalvelage was born on April 21, 1923 in Nuremberg, Germany. Kalvelage described her father as a “raging atheist who was extremely and verbally angry with organized religion” and her mother as a “lukewarm Lutheran” ….As a teenager during World War II she lived through years of aerial bombings, in her own words, “always ready to jump out and grab a satchel with important papers and go down into the basement, hoping our city wouldn’t be the one with its name on the bombs.”

A short while later when I applied, to be a GI bride,

an American consular official questioned me.

He refused my exit permit; said my answers didn’t show

I’d learned my lesson about responsibility.Thus suddenly I was forced,

To start thinking on this theme,

And when later I was permitted to emigrate,

I must have been asked a hundred times,

where I was and what I did

in those years when Hitler ruled our state.I said I was a child, or at most a teenager,

But this always extended the questioning.

Theyd ask where were my parents, my father? my mother?

And to this, I could answer not a thing.

“In 1947 the Americans claimed every German was guilty,” Kalvelage recalls, “and I took it to my heart.” When she immigrated to the United States in 1948 to marry Bernard Kalvelage, a member of the U.S. Air Force whom she’d met after the war ended, she was determined to bring greater understanding of the horrors of war to everyone who asked questions or was willing to listen.

The seed planted there in Nuremberg,

In nineteen forty-seven,

Started to sprout and to grow.

Gradually I understood what that verdict meant to me,

When there are crimes that I can see and I can know.And now I also know what it is to be charged with mass guilt —

Once in a lifetime is enough for me.

No, I could not take it for a second time —

And that is why I am here today.

With the Vietnam War raging and the number of casualties rising daily, Kalvelage also joined the San Jose Peace Center. On May 25, 1966, acting on a tip from a journalist friend, Kalvelage and three other women staged a protest at a storage yard in Aiviso, California. Carrying picket signs and dressed conservatively with hats and gloves to counter the stereotype of peace activists as long-haired hippies, the four housewives sat down in front of a forklift loaded with napalm destined for Vietnam. After a tense showdown with the forklift operator and his vicious dogs, the police and media arrived. The women were arrested, tried, and convicted of “trespassing to interfere with legal business.” A jury found them guilty but their ninety-day jail sentences were later suspended.

The events of may twenty-fifth,

The day of our protest,

Put a small balance weight on the other side.

Hopefully some day,

My contribution to peace

Will help, just a bit, to turn the tide.

The story gained international attention. At the trial, Kalvelage invoked the Nuremburg principles and her eloquent statement at a later press conference became folk singer Pete Seeger’s song, “My Name Is Lisa Kalvelage.”

Kalvelage has been a vocal critic of the Iraq war since its inception. Now in her eighties, she continues to attend peace rallies and protest marches. “I have this philosophy,” she told the Cupertino Courier in a 2003 interview. “You live until you die.”

Link for all quoted biographical text.

And perhaps I can tell my children six,

And later, on their own children,

That at least in the future,

They need not be silent,

When they are asked,

“Where was your mother, when…. ?”Kalvelage/Seeger

*****************************************************************************

The San Jose Peace & Justice Center co-produced a documentary, “Napalm Ladies,” that tells the story of Lisa Kalvelage and her collaborators. It’s well worth thirty minutes of your time. Napalm Lady Joyce McLean is a wonderfully articulate interlocutor. Pete Seeger sings “My Name Is Lisa Kalvelage” at 11:25 on the second video, although, sadly, it cuts off a few seconds before the end.

Lisa Kalvelage died on March 8, 2009. I memorized Pete’s song simply by listening to it over and over. It sustains and motivates me still.

—————————————————————————————————

I’ve not been much good as an activist, I suspect. I demonstrated against the war in Iraq. I volunteered for the Clamshell Alliance in their work against the Seabrook nuclear plant. I walked in a “Take Back The Night” march, holding up a big sign that said “Misogyny is Misanthropy” on one side and “Crimes Against Women are Crimes Against All Of Us” on the other. I’ve written countless letters to the editor and letters to my congressman and letters to the President. I’ve produced benefit concerts and raised money. I’ve canvassed and phonebanked and attended meetings and volunteered and donated and donated and donated and donated….

But I’ve also spent years wrapped up in my own artistic work, only recently waking up to the shocking likelihood that all of it — all that hard-won virtuosity in an exotic musical genre, all those innovations in compositional technique, all the originality and profundity of my scholarship — will probably be irrelevant in a world reduced to cruel essentials by catastrophic environmental failure and the howling demons of societal insanity. Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas. Oh, well.

In the past few years I’ve realized the horrors that the world is about to undergo, and my mood has grown often bleak. My daughter turned nine in January and she thinks I can do anything and fix anything. But I can’t fix this political system any more than I can fix the climate, which means that my smiles are saved for the moments when I feel her gaze upon me.

To my mind, the greatest crime that I can see and I can know is the unwillingness of our political and economic power structures to address the looming, slow-motion cataclysm that is global warming. In order to preserve the profit margins of a tiny few and the temporary comfort of a slightly larger few, the many, including non-human lives beyond measure, are to be sacrificed.

All of us in the industrialized world are complicit in this; we drive, we take long hot showers, we buy consumer goods that we don’t need; we waste food and energy; we demand convenience in all things. And now I also know what it is to be charged with mass guilt, and I am determined that not a day shall go by without my doing something that might help, just a bit, to turn the tide.

I don’t know how it will all turn out in the long run. In the long run we are all dead. But at least in the future, my daughter need not be silent when she is asked, “Did your parents know about global warming? Did they do anything about it?” Should there be a global climate court where our waste and irresponsibility would face judgment (and I do hope there is, and soon) she will have something to say at the bar of justice.

It’s not much, but it’s what I’ve got. When it seems like Fierce Audacity has given way to Weary Capitulation, and I need a reason to continue, I think of my daughter. She’s a great kid. I love her to pieces.

I’m not much of an activist, but whatever little bit of an activist I am, I owe to Lisa Kalvelage, and to Pete Seeger, who sang me her story. And to my little girl, whose life stretches out in front of her, full of promise.