Consider a finely sharpened blade, slicing through a piece of wood in a cabinet-maker’s workshop. The chisel’s razor tip is parting the fibers, supported by a substantial piece of steel which lends that keen edge all its strength, and without which carving is impossible. To exclaim over a beautiful piece of joinery is to extol not just the cutting edge, but the strength and integrity of the shaft and handle that allows the artisan to work.

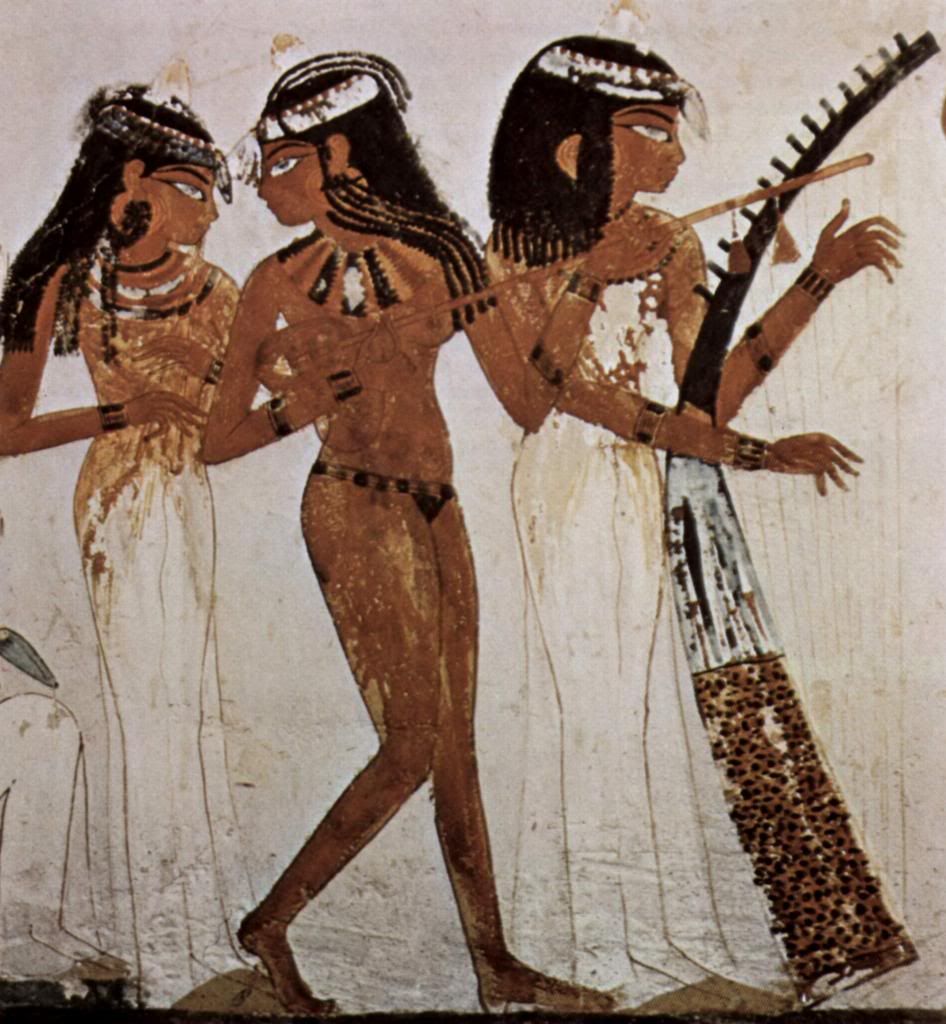

Any of us who practice, teach, and perform music are likewise supported by the labor and love of thousands of generations of our forebears. Because music is one of the oldest universal human activities (pre-dating language if Bernie Krause’s model is accurate), our participation in the power and glory of patterned sound is a link to the earliest days of our proto-human existence.

This awareness is part of what pulls us into musicking; it’s part of why, even in the most parlous of times, we sing, hum, tap our fingers and feet, and spend precious time teaching songs and melodies to our children and friends — time which we could be using on more immediately obvious benefits. But this awareness is more than a mystical connection to our species’ pre-history.

It’s also a call to action and activism.

An economic analysis of any high art tradition will reveal that vast numbers of ordinary people were systematically exploited so that those in the ruling class could engage in various forms of conspicuous consumption. European peasants suffered by the millions to support the courts and churches which in turn provided employment for the very small number of composers and musicians whose work now forms the canon of Western classical tradition. Indian peasants were likewise brutalized to support the music-loving maharajas whose patronage nurtured the obsessively-practicing master musicians whose genius created the tonal world of raga.

This history of economically oppressed serfs is not an argument against the art forms those miserable millions helped develop with their ceaseless, inadequately rewarded labor, and short, brutal lives. To reject these classical traditions for reasons of historical class injustice is to negate the last scraps of meaning and joy those peasants could offer; they gave their time on earth unquestioningly to the benefit of their feudal overlords, whose culture in turn created structures of timeless elegance and beauty.

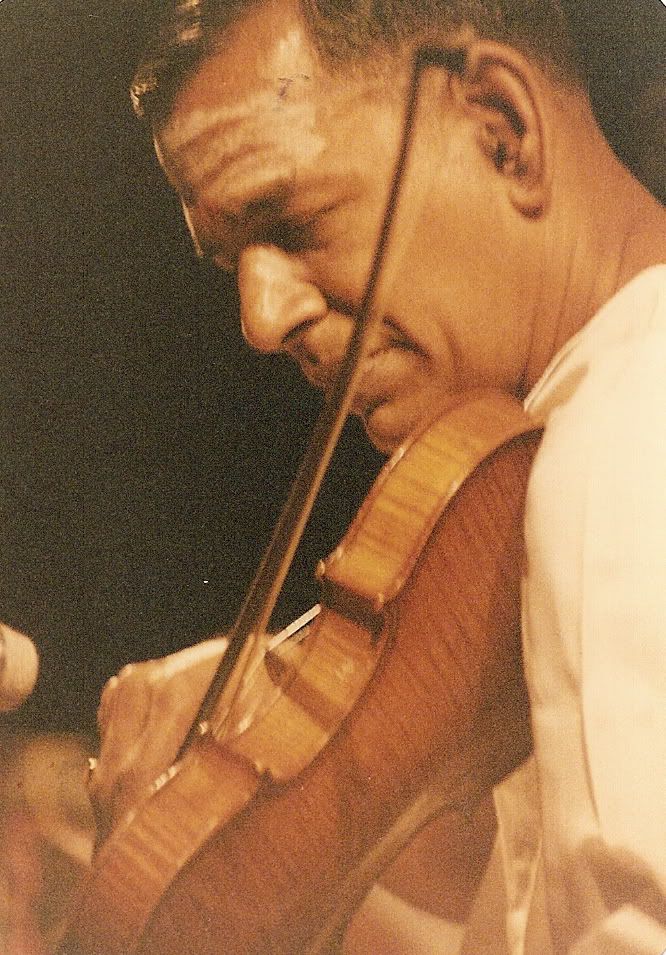

No, this history is an argument for those art forms. But we need to recognize that it wasn’t just Bach who created Bach’s music; it wasn’t just Mozart who created Mozart’s music; it wasn’t just Tansen who created ragas like Darbari Kanada and Mian ki Malhar. We bear a responsibility to the faceless and voiceless millions who contributed their entire lives in silence to support the system which nurtured these idioms to their glorious fruition.

And that responsibility is our call to engagement with the battles of our time.

Alice Walker famously said, “Activism is my rent for living on the planet.”

We musicians not only get to live on the planet, we get to play music on it — and there are faceless billions of long-dead humans whose lives helped make this possible.

Everything we do is built on the foundation they provided; it’s up to us not to squander this inheritance. Hence the call for us to become climate activists, and the necessity of finding the spot where our musical inheritances and activist responsibilities intersect. In performance, we can acknowledge their struggle-filled lives by singing and playing with complete commitment, by refusing to waste a single precious moment of music. And the rest of the time?

That’s why we are asking you to be part of The Climate Message.