In 1986, a friend and I traveled to Kashmir, which had not yet become a problematic destination for Western tourists. I had been bewitched by Kashmiri music since first hearing David Lewiston‘s wonderful recordings on the Nonesuch Explorer label in the mid-1970s, and I knew that I wanted to see and hear Kashmir for myself.

Cradled in the lap of majestic mountains of the Himalayas, Kashmir is the most beautiful place on earth. On visiting the Valley of Kashmir, Jehangir, one of the Mughal emperors, is said to have exclaimed: “If there is paradise anywhere on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here.”

Link

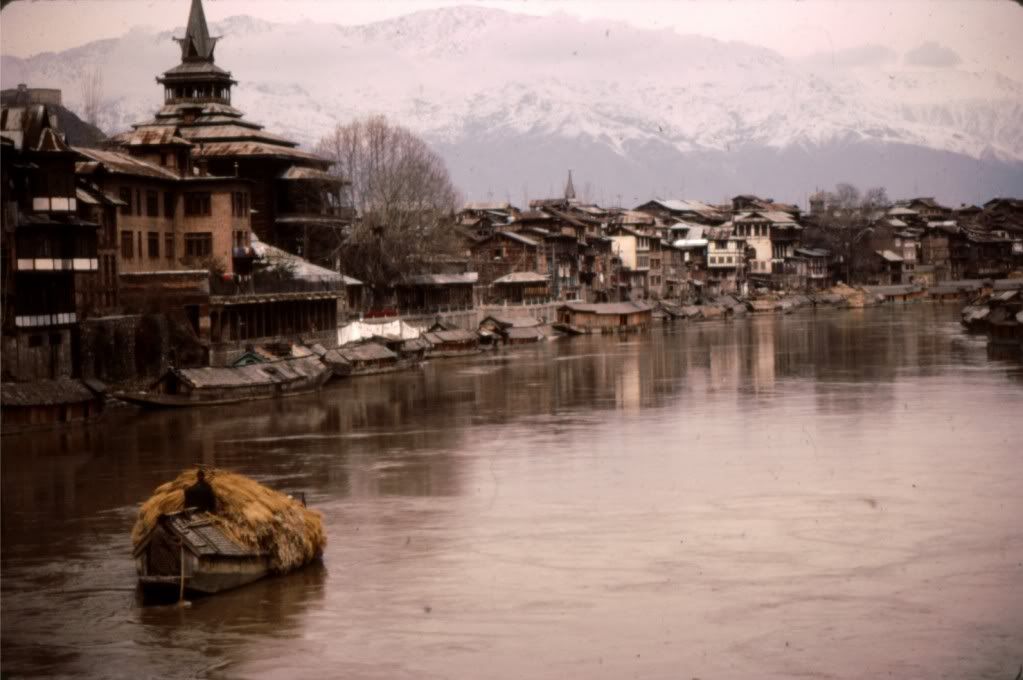

We wound up in Kashmir in March, which was a little early for tourist season. The flowers weren’t really blossoming in full force, and the city of Srinagar was just waking up from the winter. But that was okay; I didn’t really care about going trekking in the mountains. I love cities, and Srinagar was wonderful.

Kashmiris commonly wear pherans, comfortable wool poncho/capes. Note the bulge under the woman’s garment: she’s not misshapenly pregnant, she’s carrying a kangri, a small charcoal brazier filled with glowing coals and hanging from a small harness. On cold days it’s not uncommon for people to wear several of these portable heating units.

The river Jhelum runs through the middle of Srinagar; heavily laden boats move up and down. While the tourist houseboats are almost all floating in the Dal lake, there are many residential houseboats moored on the banks of the river.

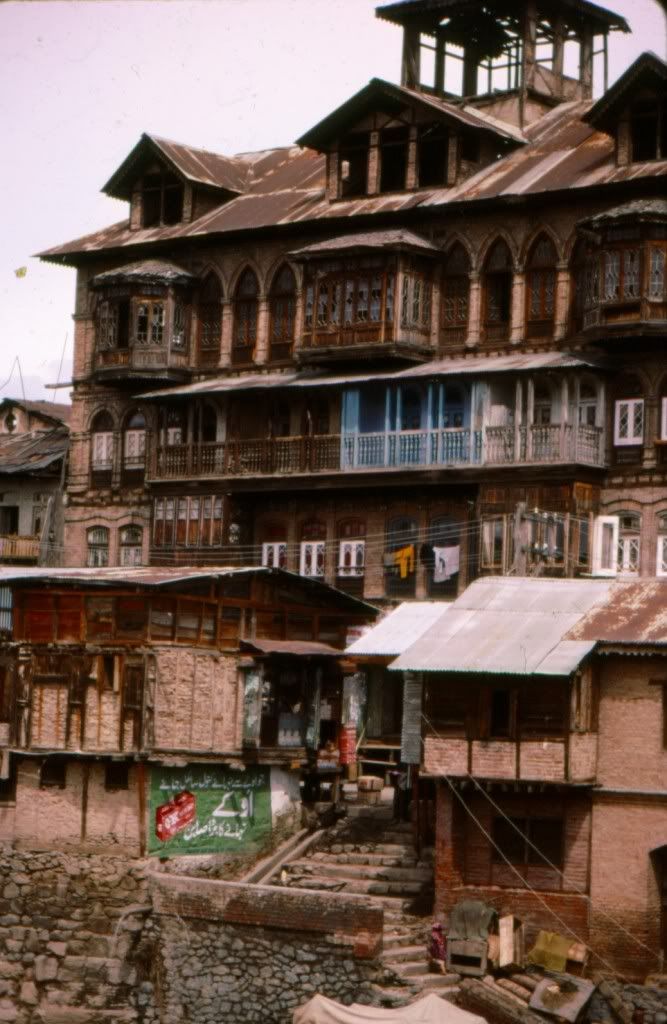

I greatly enjoyed the buildings that lined the river. Multi-story residential constructions, they seemed to have grown up accretively, one or two rooms at a time.

If you’re not trekking, a lot of what you do when you’re a tourist in Kashmir is laze around in a boat on the Dal lake. Vendors come up to you and sell you everything imaginable from their boats: t-shirts, incense, antiques, flowers… Floating on the water, looking up at the awe-inspiring mountains. It just doesn’t get any better than that.

Of course, twenty-eight years later, it’s gotten worse than that, thanks to the metastasizing greenhouse effect:

Faced with increasing frequency of droughts, and with irrigation facilities available to less than half the farms, rice farmers in Kashmir are wondering how to deal with water shortage.

“Effective measures are needed to combat frequent droughts. Though the agriculture department has constructed ponds in some areas for water harvesting, much more has to be done to ensure that farmers in all areas avail the facility of harvested water for irrigation,” says Khaliq Lone, a farmer in north Kashmir’s Nutnusa village.

According to him farmers are now “sick” of the erratic weather conditions. “Over the last few years we have been witnessing quite strange weather conditions. Droughts have become frequent while rains occur erratically.” Lone’s plight is shared by his fellow farmers all across Kashmir.

These farmers have reasons to worry. Scientists in this Himalayan region in north India have found that increase in temperature and a considerable reduction in rainfall and snowfall will result in a sharp decrease in rice yields across Kashmir, where rice is grown in more than 75% of the total agricultural land.

Another popular tourist attraction was the “floating bazaar.” One morning a week (for some reason I recall it as a Wednesday, although I have no reason to trust myself after all these years) there is a sort of “farmer’s market” where people sell vegetables from their boats, haggling, joking, yelling, calling out prices…while a few hardy tourists watch from the outskirts. It was pretty cold that morning and we were the only tourists present, which was excellent; being ignored is among the greatest pleasures of travel.

It’s not just rice that’s under threat. Tourism is facing some severe problems from glacial melting:

Receding glaciers in Kashmir are clearly showing the signs of a warming climate caused by a shrinking forest cover and ecological degradation.

Climate change is drastically eating away glaciers in Indian-administered Kashmir, setting alarm bells ringing among the environmentalists.

The scenic Kashmir Valley is home to some 60 of the 327 major glaciers in Himalayas that contribute to 75% of the water in the rivers of Indus Water basin.

And signs of melting of the glaciers at a faster rate are quite visible, according to an ongoing study by experts from Kashmir University (KU). The study makes it amply clear that glaciers are melting due to an unusual increase in temperature in the region.

For instance, in Suru basin (in Ladakh region of Kashmir), a tributary of the Indus river, the loss in glacier cover has reached nearly 17%. “We have studied data of the last 40 years. Fourteen smaller glaciers in Suru Valley have already vanished and the overall loss is about 16.43%,” says Dr Shakil Romshoo, a system analysis expert and an associate professor at the KU’s Geology and Geophysics Department.

But enough with the pretty pictures. Let’s go check out some music, shall we?

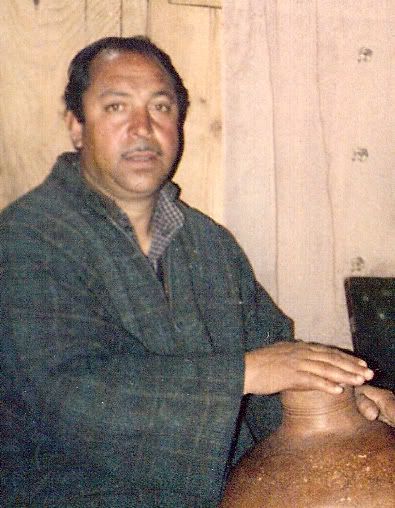

I asked the owner of the houseboat where we were staying to find me music and musicians. He was a trifle taken aback; most tourists are happy enough to hear Kashmiri music in their hotels, but don’t go actively seeking it. But tourism-based economies are all about supplying what the customers want, and a day later he told me that a session had been arranged. A guide came and got us in a cycle-rickshaw, and we rode to the banks of the Jhelum and walked down a small set of steps to a landing, where we boarded the houseboat of Ghulam Mohammed Ahangir, one of the three musicians who had agreed to perform for us. He seemed to be the musical director of the trio, dividing his time between singing, playing a small reed harmonium and providing rhythmic accompaniment on the nuht, an earthenware pot played by slapping and tapping across the sides and opening.

G.M. Ahangir, playing the nuht.

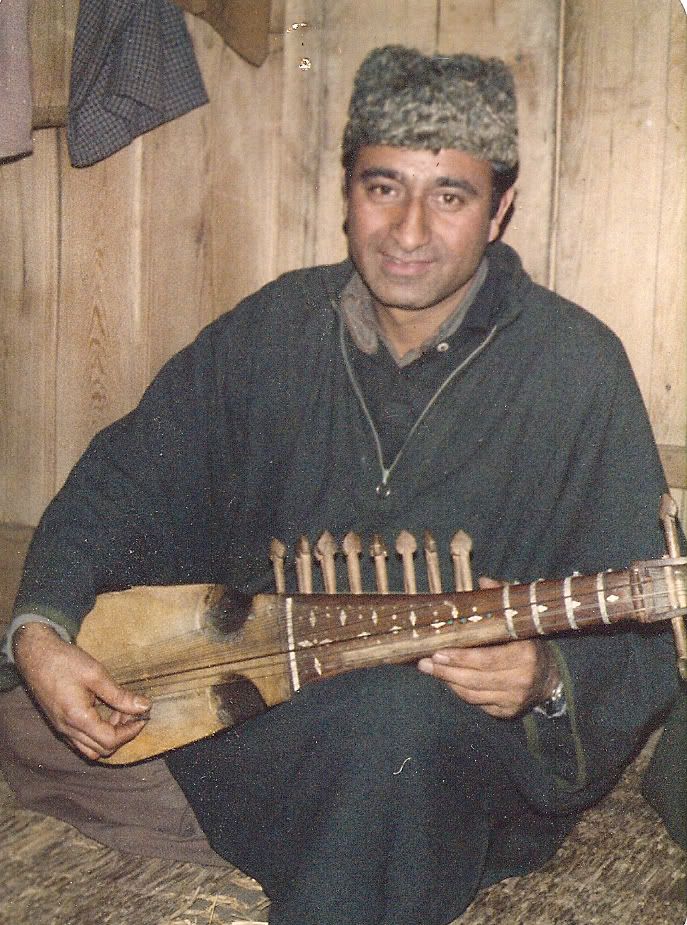

An instrument that I’d always loved is the Kashmiri Rabab, and I was delighted to meet Moi-ud-din Bhat, the rababiya for the evening. The Rabab is a plucked stringed instrument with a skin head, which gives it the projection and bright tone of a banjo. There are a few frets made of gut, tied on at the base of the neck. You’ll see two small semi-circular notches along the body of the instrument; these are reminders of the rabab‘s past as a vertically played fiddle in Arabic and Persian music. As the instrument traveled into India through Afghanistan, it lost the bow somewhere in the Hindu Kush and began to be played with a plectrum. In Indian classical music, the beautiful sarod is a direct descendant of the rabab.

Moi-ud-din Bhat, playing the Kashmiri Rabab.

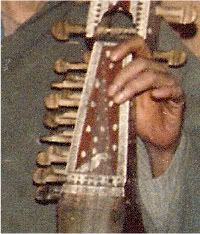

The third member of the trio was Abdul Aziz Parvez, who specialized in the Kashmiri Sarangi, a bowed instrument with a bright, resonant tone that belies its small size. The sarangi is common throughout North India; there are many folk versions as well as the “classical” sarangi found in Hindustani concert performances. The sarangi is played by touching the strings sideways with the cuticle; there is never any downward pressure exerted by the player’s left hand.

A closeup of Abdul Aziz Parvez’ left hand.

Abdul Aziz Parvez, playing the sarangi.

I recorded almost 90 minutes of music that evening, and the tape that resulted has continued to be a personal favorite over the ensuing decades. The musicians began with a medley of traditional Kashmiri melodies. The tunes they strung together had no titles; Ahangir noodled a bit on the harmonium, settled on a line and began playing it over and over until everybody joined in. They kept it up until the melody began to lose its power, at which point they all took a breath and started a new one. This piece was almost twenty minutes long, and allowed them to get their ears and instruments limbered up and synchronized. After that they presented some songs in the Kashmiri language, some shorter instrumental pieces, and a piece of Soofiyana Qalam (Sufiana Kalam), the Kashmiri version of traditional North Indian classical music.

Note: The videos combine the music I recorded with the photographs I took; I’ve included three in the body of this piece, but if you want to listen further, just investigate the “related videos.”

Here is a trio: rabab, sarangi and nuht:

Here’s a traditional Kashmiri song:

And here is some Soofiana Qalam:

Life in Kashmir offers many extraordinary points of beauty. But the transforming climate is making it harder for everyone, in every way:

Every morning Farida Akhtar wakes up, she peeps through the window, before casting a look at the clock, to see if there is any probability of a sunny day ahead. The past four days of complete sunshine have brought relief to her, first time in the past two and a half months.

She has no idea why the weather is turning too erratic with each passing year. “Every year it springs a surprise,” she says. “Last year we had an exceptionally hot summer followed by an extremely cold winter; and now a long spell of rains and windstorms,” says 44-year-old Akhtar, a house-wife who lives in Bemina, Srinagar.

For Kashmiris, it is the start of second fortnight of June that marked the actual beginning of summer this year. The charm of spring in April and May was almost absent because of an extended spell of erratic weather which also brought devastating windstorms at regular intervals.

In March this year a destructive windstorm, which lasted for four consecutive days, wrecked havoc across Kashmir. The storm, according to official estimates, killed five people and injured another 35, apart from causing damage to 9214 residential houses, 235 were completely destroyed.

“I have never seen such a windstorm in my life which would last for days together,” says 67-year-old Sonawallah Rather of Pattan. Before the windstorm of early spring, people in Kashmir had to repeatedly hear about snow avalanches and landslides claiming lives and damaging infrastructure in the hilly areas because of heavy snowing.